Containers to the Edge: 2018 → 2025

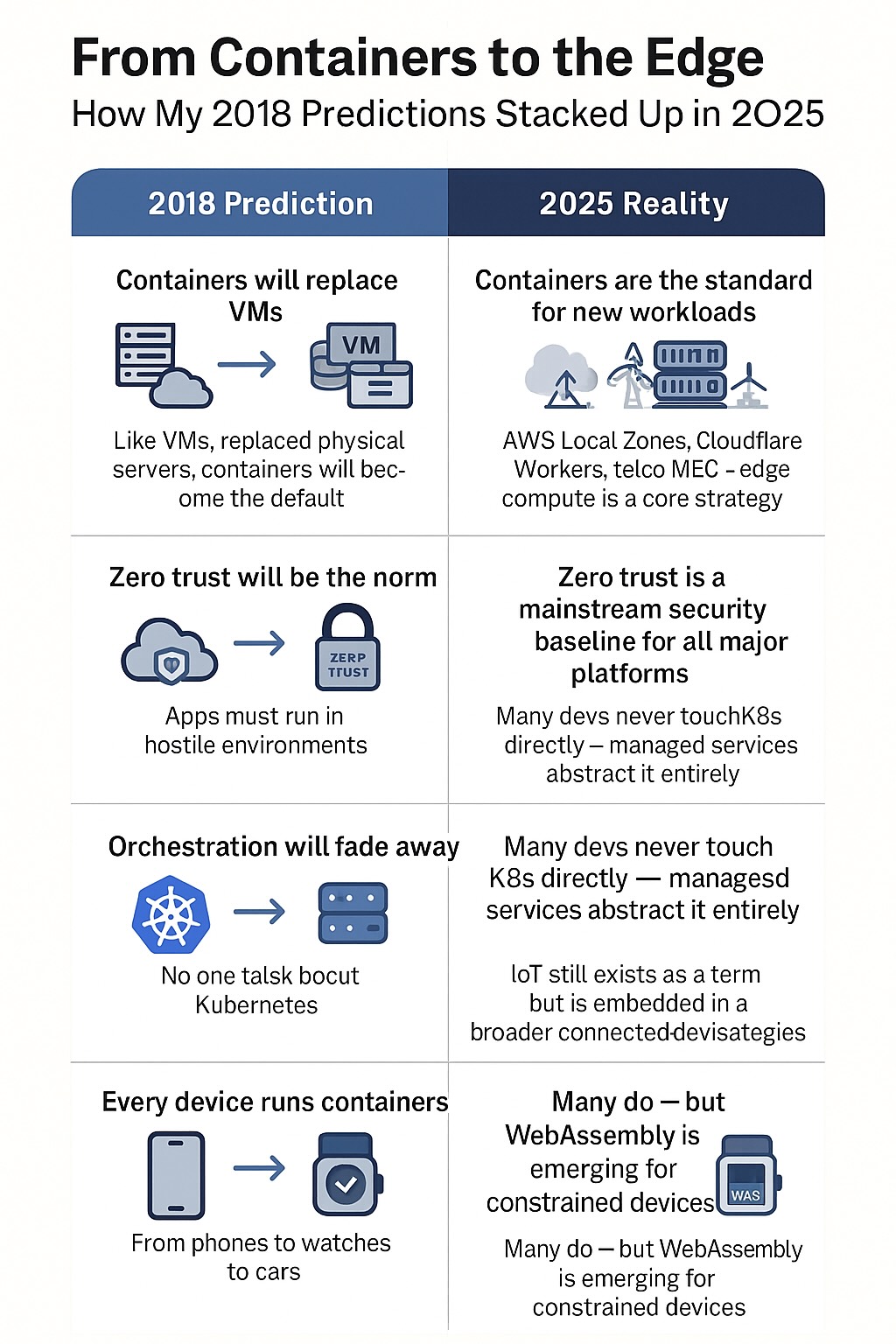

In 2018, I argued that container orchestration would fragment, not consolidate. Seven years later, here's where that thesis landed.

What I Wrote in 2018

In late 2018, Kubernetes was ascendant. The consensus was clear: container orchestration had found its winner, and everyone else would either adopt Kubernetes or fade into irrelevance.

I wrote that this was wrong.

Not because Kubernetes wouldn't dominate—it would. But because the "one orchestrator to rule them all" vision missed what was actually happening: containers were moving to environments where Kubernetes made no sense.

Edge computing. IoT gateways. Single-board computers. Constrained environments where running a control plane designed for cloud-scale clusters was absurd.

The thesis was that container orchestration would fragment by deployment target. Kubernetes would win the datacenter and cloud. Everything else would splinter into specialized tools optimized for their specific constraints.

* * *What Actually Happened

By 2025, Kubernetes is ubiquitous in exactly the places I predicted it would be: cloud platforms, enterprise datacenters, and anywhere infrastructure teams have the resources to operate complex control planes.

It also became the standard that everyone claims compatibility with—even when they're not actually running Kubernetes.

The Fragmentation Arrived

But the thesis held. Container orchestration fragmented along deployment boundaries:

Edge and IoT diverged. K3s, MicroK8s, and eventually serverless container platforms emerged for edge deployments. They claimed Kubernetes compatibility, but they weren't Kubernetes—they were Kubernetes-shaped enough to reuse tooling while stripping out everything that didn't fit resource-constrained environments.

Serverless captured the developer workflow. AWS Fargate, Google Cloud Run, and Azure Container Instances gave developers container deployment without cluster management. They abstracted Kubernetes away entirely, delivering containers as a service rather than containers as an orchestration problem.

Embedded systems went custom. Industrial IoT, autonomous vehicles, and manufacturing systems built their own container runtimes. They needed deterministic behavior, real-time guarantees, and stripped-down attack surfaces that general-purpose orchestrators couldn't provide.

Developer tools reinvented local orchestration. Docker Compose refused to die. Docker Desktop, Podman, and local development tools kept containers without Kubernetes alive because developers didn't want to run a control plane just to test a microservice.

The Winner and the Fragments

Kubernetes won the war for infrastructure orchestration. But it didn't win the war for container deployment.

What happened instead was layering: Kubernetes became the infrastructure abstraction that other platforms built on top of. It became invisible to developers, hidden behind managed services, serverless platforms, and PaaS offerings that delivered containers without exposing cluster complexity.

The fragmentation wasn't competitors to Kubernetes. It was specializations around it.

* * *The Pattern That Holds

This is what repeats across infrastructure cycles:

Consolidation happens at the infrastructure layer. One orchestrator, one control plane, one standard dominates the layer where infrastructure teams operate. This is inevitable because infrastructure needs common abstractions to function at scale.

Fragmentation happens at the deployment layer. The moment infrastructure moves into specialized environments—edge, embedded, real-time, constrained—the "one size fits all" solution fractures. Not because the standard fails, but because the deployment constraints don't match the assumptions the standard was built on.

Abstraction wins by hiding complexity. Developers don't want to manage orchestration. They want to deploy code. The winners aren't the platforms with the most powerful orchestrators—they're the platforms that make orchestration invisible.

Specialized tooling emerges for specialized constraints. Every time a new deployment target appears with different resource constraints, latency requirements, or operational models, new tooling emerges. The standard doesn't extend; it gets wrapped, simplified, or replaced for that context.

* * *Why This Matters for Autonomous Agents

If you're evaluating agent orchestration platforms, pay attention to this pattern.

There will be a standard. Something will emerge that becomes the "Kubernetes of agent orchestration"—the control plane that infrastructure teams rally behind for managing autonomous systems at scale.

But that standard won't be what developers use to deploy agents.

Deployment will fragment by context: agents running on edge devices won't use the same orchestration as agents running in cloud clusters. Agents embedded in SaaS products won't share infrastructure with agents managing internal workflows. Real-time agents with microsecond latency requirements won't run on the same platforms as batch-processing agents that optimize for cost.

The pattern repeats: consolidation at the infrastructure layer, fragmentation at the deployment layer, abstraction winning by hiding complexity.

What matters isn't picking the orchestrator that will win. It's understanding where your agents actually need to run, what constraints they operate under, and whether the platform you're evaluating is optimized for infrastructure teams or deployment reality.

Most will optimize for the infrastructure layer. That's where the vendor incentives are.

The ones that win will optimize for deployment—and make the infrastructure invisible.

← Back to Patterns That Repeat